Alan Feraday

Alan or Allen Feraday (born 23 December 1937), former head of the Forensic Explosives Laboratory (FEL) at the Royal Armaments Research and Development Establishment (RARDE) at Fort Halstead in Kent, is a self-professed forensic expert in electronics.[1]

Although not academically qualified for the role, Alan Feraday was often addressed as ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’ when he appeared as an expert electronics witness in a number of high profile terrorist bombing cases including Danny McNamee (1982), John Berry (1983), Patrick Magee (1984), Hassan Assali (1985), the Gibraltar shootings (March 1988) and the Lockerbie bombing (December 1988).

Margaret Thatcher soon took an interest in Alan Feraday after his evidence in the 1986 Brighton bombing case where Patrick Magee was convicted, and was especially grateful for the exculpatory testimony Feraday gave at the "Death on the Rock" inquest in Gibraltar, when the SAS were alleged to have been operating a "shoot to kill" policy against three IRA bombers killed in March 1988.[2]

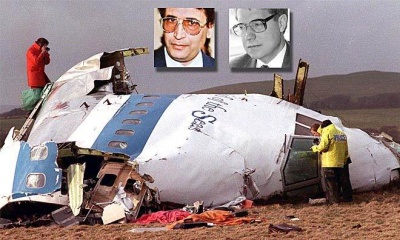

Following the sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103 on 21 December 1988, the director of the Forensic Explosives Laboratory Dr Thomas Hayes and his colleague Alan Feraday were tasked with the forensic investigation into the Lockerbie bombing, which was allocated the FEL case reference number PP8932. In the 1989 Queen's Birthday Honours list, Feraday was awarded an OBE and took over as head of the FEL when Hayes retired to become a chiropodist in the latter part of 1989. Two years later, Feraday and Dr Hayes (who continued with the Lockerbie investigation on a part-time basis) compiled a Joint Forensic Report into case PP8932. The JFR identified the only piece of hard evidence in the Lockerbie case: a tiny fragment of printed circuit board that Feraday maintained had been the trigger for the Lockerbie bomb.

On 28 September 1993, Alan Feraday’s career prospects suddenly appeared to be in tatters when, in overturning John Berry's conviction, England's most senior judge, the Lord Chief Justice Lord Taylor of Gosforth, commented that although Feraday's views were "no doubt honestly held", his evidence had been expressed in terms that were "dogmatic in the extreme" and his conclusions were "uncompromising and incriminating". LCJ Taylor went even further saying that in future Feraday should not be allowed to present himself as an expert in the field of electronics.[3][4]

In 1995, Alan Feraday saw the writing on the wall and, aged 58, took early retirement after 25 years' service at the FEL when RARDE was subsumed into the less regal-sounding Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA).[5]

How come then the main prosecution 'expert' witness at the trial in June 2000 of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi – who was convicted in January 2001 of the Lockerbie bombing – was none other than Alan Feraday? The obvious answer is that Scots Law Professor Robert Black arranged for the trial to be held in the Netherlands under Scottish Judges, where Feraday's ban imposed by the English Law Lord could safely be ignored.[6]

Contents

Expert witness

Alan Feraday has appeared as an expert witness at criminal trials leading to convictions in at least six high-profile cases, three of which were subsequently overturned on appeal. In September 2009, human rights lawyer Gareth Peirce wrote:

- This isn’t the first time we have heard of Hayes and Feraday. Among the many wrongful convictions in the 1970s for which RARDE scientists were responsible, Hayes played his part in the most notorious of all, endorsing the finding of an explosive trace that was never there, and speculating that a piece of chalk mentioned to the police by Vincent Maguire, aged 16, and a candle by Patrick Maguire, aged 13, ‘fitted the description better’ of a stick of gelignite wrapped in white paper. Both were convicted and imprisoned on this evidence, together with their parents and their uncle Giuseppe Conlon, who was to die in prison. All were later found to be innocent.

- Although Feraday was often addressed by the prosecution as ‘Dr’ or ‘Professor’ when he gave evidence, he had no relevant academic qualifications, only a higher national certificate in physics and electronics some 30 years old. Dr Michael Scott, whose evidence has been preferred in appeals to that of Feraday, commented that:

"The British government employed hundreds of people who were extraordinarily well qualified in the areas of radio communication and electronics. Alan Feraday is not qualified yet they use him. I have to ask the question, why?"

- Alan Feraday, like his US counterpart Thomas Thurman, has now been banned from future appearances as an expert witness, but he had already provided the key evidence in a roll-call of convictions of the innocent. A note of a pre-trial conference with counsel prosecuting Danny McNamee (who was wrongly convicted of involvement in a bombing in Hyde Park) provides a typical instance:

"F [Feraday] prepared to say it [a circuit board] purely for bombing purposes, no innocent purpose."

- The implication here was that anyone who had involvement with this circuit board would have knowingly been involved in bomb construction. That, in common with many other assertions made by Feraday, was entirely false, but it resulted in McNamee’s imprisonment for 11 years.

- To discover that al-Megrahi’s conviction was in large part based on the evidence of scientists whose value as professional witnesses had been permanently and publicly demolished ten years before his trial is astounding. The discovery nearly two decades ago of a large number of wrongful convictions enabled by scientific evidence rightly led to demands that the community of forensic scientists change its ways.[7]

Caddy Inquiry

On 9 December 1996, a Labour MP posed the following Parliamentary Question:

- Mr Kevin McNamara: To ask the Secretary of State for the Home Department if he will list the names of the 14 cases, representatives of which have received notification that they are being reviewed as part of Professor Caddy's inquiry; and in which cases Mr Alan Feraday was a Crown witness.

- Home Secretary Michael Howard [holding answer 4 December 1996]: The representatives of the following individuals were advised that their cases would be examined by Professor Caddy as part of his inquiry.

- James Canning

- Derek Donerty

- Robert Fryers

- Patrick Hayes

- Hugh Jack

- Denis Kinsella

- John Kinsella

- Ethel Lamb (deceased)

- Pairic MacFhloinn

- Sean McNulty

- Gerard Mackin

- Nicholas Mullen

- Jan Taylor

- Vincent Wood.

- My right hon. and learned Friend the Attorney-General will write to the hon. Member in relation to those cases in which Mr Alan Feraday was a Crown witness.[8]

On 17 December 1996, the House of Commons debated the Caddy Inquiry into the Forensic Explosives Laboratory at Fort Halstead.

- Mr Kevin McNamara (Kingston upon Hull, North): The whole House will be indebted to Professor Caddy for his report. He is a distinguished forensic scientist (Director of the Forensic Science Institute at Strathclyde University).

- The Home Secretary said that he saw no grounds for referring cases to the Court of Appeal, but he appeared to anticipate that, when legal representatives of convicted people obtain copies of the report, they might seek to go to the Court of Appeal again on the basis of what is in the report. First, as many hon. Members have not had an opportunity to examine the report, will the Home Secretary tell the House why he feels that those people may seek to go to the Court of Appeal again?

- Secondly, he will recall that, in a recent case, a senior official in the forensic science service (Mr Alan Feraday) was highly criticised for his lack of qualifications by, I believe, the Lord Chief Justice on appeal. Is that person involved in any of those cases?

- Home Secretary Michael Howard: The hon. Gentleman was reading rather too much into my remarks. As I said, I do not believe that any grounds arising out of this report would justify any of the cases concerned being referred to the Court of Appeal.

- However, I have learnt over a long period not to underestimate the ingenuity of lawyers. I said that it was open to representatives of those involved in those cases to make further representations suggesting that the cases should be referred, and that any such representations would be considered.

- I do not have available a specific answer to the last part of the hon. Gentleman's question. I have no reason to suppose that the person to whom he referred (Mr Alan Feraday) was involved, but perhaps I can write to the hon. Gentleman on that matter.[9]

Commentary on Feraday

On 15 June 2000, Alan Feraday testified as an 'expert witness' against Abdelbaset al-Megrahi at the Lockerbie trial. Professor Black and Ian Ferguson recorded this commentary on Feraday:

- As one of the Crown's key witnesses gave his testimony this week in Camp Zeist at the trial of the two Libyans accused of the bombing of Pan Am 103, one man, Hassan Assali watched news reports with interest as Allen Feraday took the witness stand.

- Assali, 48, born in Libya but who has lived in the United Kingdom since 1965, was convicted in 1985 and sentenced to nine years. He was charged under the 1883 Explosives Substances Act, namely making electronic timers.

- The Crown's case against Assali depended largely on the evidence of one man, Allen Feraday. Feraday concluded that the timers in question had only one purpose, to trigger bombs. While in Prison Assali, met John Berry, who had also been convicted of selling timers and the man responsible for leading the Crown evidence against Berry was once again, Feraday.

- Again Feraday contended that the timers sold by Berry could have only one use, terrorist bombs.

- With Assali's help Berry successfully appealed his conviction, using the services of a leading forensic expert and former British Army electronic warfare officer, Owen Lewis.

- Assali's case is currently before the Criminal Cases review Commission, the CCRC. It has been there since 1997. Assali believes that his case might be delayed deliberately, as he stated to the Home Secretary, Jack Straw in a fax in February 1999:

- "I feel that my case is being neglected or put on the back burner for political reasons"

- Assali believes that if his case is overturned on appeal during the Lockerbie trial it will be a further huge blow to Feraday's credibility and ultimately the Crown's case against the Libyans. There is no doubt that a number of highly qualified forensic scientists do not care for the highly "opinionated" type of testimony, which is a hallmark of many of Feraday's cases.

- He has been known, especially in cases involving timers to state in one case that the absence of a safety device makes it suitable for terrorists and then in another claim that the presence of a safety device proves the same, granted that the devices were different, but it is the most emphatic way in which he testifies that his opinions are "facts", that worries forensic scientists and defence lawyers.

- In his report on Feraday's evidence in the Assali case, Owen Lewis states,

- "It is my view that Mr Feraday's firm and unwavering assertion that the timing devices in the Assali case were made for and could have no other purpose than the triggering of IED's is most seriously flawed, to the point that a conviction which relied on such testimony must be open to grave doubt."

- A host of other scientists, all with vastly more qualifications than Feraday concurred with Owen Lewis.

- A report by Michael Moyes, a highly qualified electronics engineer and former Squadron Leader in the RAF, concluded:

- "there is no evidence that we are aware that the timers of this type have ever been found to be used for terrorist purposes. Moreover the design is not suited to that application."

- Moyes was also struck by the similarity in the Berry and Assali case, in terms of the Feraday evidence.

- In setting aside Berry's conviction in the Appeal Court, Lord Chief Justice Taylor described Feraday's evidence as "dogmatic in the extreme", his conclusions were "uncompromising and incriminating" and that in future he should not be allowed to present himself as an expert in the field of electronics.

- This week in the Lockerbie trial, Feraday exhibited that same attitude when questioned by Richard Keen QC. Keen asked Feraday about Lord Chief Justice Taylor's remarks on his evidence, but Feraday, dogmatically, said he stands by his evidence in the Berry case. He was further challenged over making contemporaneous notes on items of evidence he examined. Asked if he was certain that he had made those notes at the time, he said yes. When shown the official police log book which showed that some of the items Feraday had claimed to have examined had in actual fact been destroyed or returned to their owner before he claimed to examined them, his response, true to his dogmatic evidence was the police logs were wrong.

- Under cross-examination though, it did become clear that Feraday completed a report for John Orr (predecessor of Stuart Henderson) who was leading the Police Lockerbie investigation and in that report he stated he was:

- "Completely satisfied that the Lockerbie bomb had been contained inside a white Toshiba RT 8016 or 8026 radio-cassette player", and not, as he now testifies, "inside a black Toshiba RT SF 16 model."

- As recently as May 2000, the leading civil liberties solicitor, Ms Gareth Peirce, told the Irish Times that the Lockerbie trial should be viewed with a questioning eye as lessons learned from other cases showed that scientific conclusions were not always what they seemed. Speaking in Dublin Castle at an international conference on forensic science, Ms Peirce said she observed with interest the opening of the Lockerbie trial and some of the circumstances which, she said, had in the view of the prosecution dramatically affected the case. She asked herself questions particularly relating to circuit boards which featured in the Lockerbie case and also in a case that she took on behalf of Mr Danny McNamee, whose conviction for conspiracy to cause explosions in connection with the Hyde Park bombings (another case in which Feraday testified) was eventually quashed. She asked herself whether the same procedures were involved.

- Danny McNamee may be the most recent Feraday case to be overturned, Hassan Assali believes his case will be the next.[10]

Danny McNamee

Alan Feraday was the Crown's main scientific witness in the Danny McNamee case concerning a terrorist bomb explosion in London's Hyde Park on 20 July 1982, which killed four members of the Household Cavalry - the Queen's official bodyguard - and seven of the regiment's horses. The case against McNamee was based on the following assertions:

- Feraday testified that a fragment of printed circuit board said to have been recovered on the crime scene - but which had not been forensically tested for explosive residues - had been specifically designed to trigger a radio-controlled bomb.

- Feraday also testified that the circuit was identical to circuits recovered from an IRA cache where fingerprints of McNamee had been found on a battery.

- Finally, Feraday testified that those circuits had been built by the same person.

In 1987, Danny McNamee was sentenced to 25 years for the Hyde Park bombing despite pleading that he was innocent of the crime.

In McNamee's appeal, scientists far more qualified than Feraday exposed all three claims as utter nonsense. There was nothing specific about the circuit and it was very different in design and quality than the ones recovered at the cache.[11] In fact, Danny McNamee had a degree in electrical engineering and would have done a much better job. The presence of his fingerprints on a battery was easily explained: he had worked in an electrical store owned by an IRA member.[12]

By 1998 Danny McNamee had spent 11 years wrongfully imprisoned and, shortly after his release under the Good Friday Agreement, a judge overturned his conviction, deeming it "unsafe" because of withheld fingerprint evidence that implicated other bomb-makers.[13][14]

John Anthony Downey

In what looks like an obvious attempt by the establishment to rehabilitate Alan Feraday's fatally damaged reputation, senior Sinn Fein member John Anthony Downey has now been charged over the 1982 IRA Hyde Park bombing in London. Downey has denied all charges at his Old Bailey trial.[15]

John Downey, aged 61, from County Donegal was arrested at Gatwick Airport on 19 May 2013 and appeared at Westminster Magistrates' Court on 22 May 2013 charged with the murder of four Household Cavalry members who were killed en route to Buckingham Palace. Downey's case was sent to the Old Bailey for a bail hearing on 24 May 2013 and a preliminary hearing on 5 June 2013.[16]

John Downey's arrest provoked a strong reaction from Sinn Fein who called for his immediate release. Sinn Féin Assembly member Gerry Kelly said Sinn Féin member Downey was a "long-time supporter of the Peace Process" and should be released. Gerry Kelly added:

- "The decision to arrest and charge him in relation to IRA activities in the early 1980s is vindictive, unnecessary and unhelpful. It will cause anger within the republican community. Clearly, if John Downey had been arrested and convicted previously he would have been released under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. As part of the Weston Park negotiation, the British Government committed to resolving the position of OTRs [‘On the Runs’]. John Downey received a letter from the NIO in 2007 stating that he was not wanted by the PSNI or any British police force. Despite travelling to England on many occasions, now – six years on – he finds himself before the courts on these historic charges. This development represents bad faith and a departure from what was previously agreed by both governments. John Downey needs to be released and allowed to return home to his family."[17]

John Downey was granted conditional bail on 2 August 2013 to attend trial at the Old Bailey on 14 January 2014, where he will be represented by Gareth Peirce who famously represented those wrongly accused of the Guildford Four bombing.[18] If he has the temerity to appear as an expert witness at Downey's trial, Alan Feraday OBE should expect to face a withering cross-examination by Gareth Peirce.[19]

John Berry

Another case in which Feraday appeared as an expert witness was the 1983 prosecution of former Marine and businessman John Rodney Francis Berry, who was convicted of terrorism conspiracy charges on 24 May 1983, in the Crown Court at Chelmsford before Judge Greenwood and a jury. On 25 May 1983 he was sentenced to eight years' imprisonment. On 26 March 1984 the Court of Appeal (Dunn L.J., Stacker and Jupp JJ.) [1984] 1 W.L.R. 824 allowed the appeal and quashed the conviction. On 29 November 1984 the House of Lords (Lord Fraser of Tullybelton, Lord Scarman, Lord Diplock, Lord Roskill and Lord Brandon of Oakbrook) [1985] A.C. 246 ordered that the decision of the Court of Appeal be reversed and the conviction be restored. During the proceedings in the House of Lords the applicant absconded to Spain. On 24 February 1989 he was expelled by the Spanish authorities and arrested at London airport. On 12 October 1989 the Court of Appeal (Watkins L.J., Tucker and Morland JJ.) adjourned an appeal against sentence pending an application that the court could hear an appeal against conviction on grounds of appeal which had been argued but not decided in the Court of Appeal and which remained undecided by the House of Lords.[20] The case revolved around electronic timers, which Berry had supplied to a Syrian customer. The prosecution claimed that the devices were specifically designed for terrorist purposes and supplied in the knowledge that they would be used by terrorists. The Crown case relied largely on Feraday, who told the Court:

- "As a result of an examination of the timing device I came to the conclusion that it was specifically designed and constructed for aterrorist purpose, that is to say to be attached to an explosive device."

Berry spent ten years in jail before his conviction was overturned in September 1993, when four highly qualified expert witnesses ridiculed the evidence that Feraday had given at the trial. Their views were summed up by Dr John Wyatt who had served 23 years in the Royal Engineers, spending much of his time in bomb disposal and counter-terrorist operations, and rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He said:

- "As far as I am concerned this is only a timer, nothing else."[21]

In overturning Berry's conviction, England's most senior judge, the Lord Chief Justice Lord Taylor of Gosforth, commented that although Feraday's views were "no doubt honestly held", his evidence had been expressed in terms that were "dogmatic in the extreme", his conclusions were "uncompromising and incriminating" and that in future he should not be allowed to present himself as an expert in the field of electronics.[22]

In a recent development, the Home Office has agreed to pay compensation from the public purse to Berry because he was jailed on the erroneous evidence of Feraday.[23]

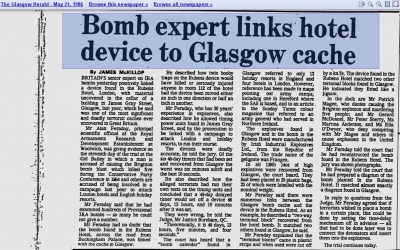

Brighton hotel bombing

The Brighton hotel bombing occurred on 12 October 1984 at the Grand Hotel in Brighton. A long-delay time bomb was planted in the hotel by Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) member Patrick Magee, with the intention of assassinating Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet, who were staying at the hotel for the Conservative Party conference. Although Thatcher narrowly escaped injury, five people were killed (including two senior members of the Conservative Party) and 31 were injured. Giving evidence at the Brighton bombing trial in May 1986, Alan Feraday said that he had examined hundreds of Provisional IRA bombs - so many he could not give a number. "The devices were deadly accurate," Feraday told the jury. "Of the six 48-day timers that had been set and recovered from Glasgow the worst was six minutes adrift and the best 10 seconds."[24]

Patrick Magee was convicted of the Brighton bombing, sentenced in September 1986 and received seven life sentences. Magee was released from prison in 1999, having served 14 years in prison, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.[25]

Hassan Assali

Libyan national, Hassan Assali, came to Britain in 1965 and established a successful electronics company in Hertfordshire. In 1984 a disgruntled ex-employee told police that Assali was making and supplying timers to an Arab diplomat for use in bombs. The police raided Assali's factory and seized a number of timers. In an echo of his evidence in the Berry trial, Feraday later testified:

- "After due consideration, I am unable to envisage any lawful domestic or military purpose for which these timer units have been prepared. I am of the opinion that they have been specifically designed and constructed for terrorist use. I am unable to contemplate their use in other than bombs."

In 1985, Hassan Assali was convicted of constructing electronic timers in contravention of the 1883 Explosives Substances Act on the basis of Feraday's testimony. Assali's appeal against conviction was rejected in 1986 and he applied to the Criminal Cases Review Commission in 1997 to review his case. After an eight-year delay, the CCRC granted Assali a second appeal saying that the strong criticism made of Feraday in the Berry judgment 'applies equally to the expert evidence he provided in Mr Assali's case'.[26] An array of expert witnesses testified at Assali's second appeal that Feraday's central claim was nonsense. One of them was retired RAF Squadron Leader Michael Moyes, a qualified electronics engineer, whose report concluded:

- "There is no evidence that we are aware of that timers of this type have ever been found to be used for terrorist purposes. Moreover, the design is not suited to that application."

In July 2005, Assali's 20-year quest for justice ended when the Crown informed the High Court that it would not contest the appeal. On 19 August 2005, BBC News Scotland reported that the criticism of Feraday's expert witness evidence in previous cases could have repercussions on Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's application to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission for a second appeal against his conviction for the Lockerbie bombing:

- "After the first case, which took place seven years before the Lockerbie trial, the Lord Chief Justice said Mr Feraday should not be allowed to present himself as an expert in the field of electronics."[27]

Alan Feraday told the Daily Telegraph:

- "I'm taking legal advice and shan't be talking to anybody."[28]

Gibraltar shootings

On 7 March 1988, three members of an IRA active service unit were shot dead by the SAS on Gibraltar. They were reported to have planted a 500lb car bomb near the British Governor's residence. It was primed to go off the following day during a changing of the guard ceremony, popular with tourists. The three - two men and a woman - were shot as they walked towards the border with Spain. Security officers say they were acting suspiciously and the officers who carried out the shootings believed their lives were in danger. The three dead were named as Daniel McCann, 30, and Sean Savage, 24, both known IRA activists and Mairead Farrell, 31, the most senior member of the gang who had served 10 years for her part in the bombing of a hotel outside Belfast in 1976.[29]

In his 1991 book, David Leppard wrote that "Feraday first came to public notice during the inquest in Gibraltar into the deaths of three unarmed IRA terrorists gunned down by soldiers from the Special Air Services (SAS)." It was a controversial action the SAS explained by each of the three reaching for their pockets or purse, presumably to detonate a car bomb they feared might exist nearby. There were no detonators, no bomb, no other weapons. Just dead IRA members, murdered, some said. Leppard explained the role of Feraday’s testimony at the inquest was "giving a scientific rationale to the controversial decision." The counter-argument, accepting the apparent plans to build a car bomb, was that the three were too far from the car in question to have triggered it, and the SAS men should have known that. But Feraday claimed from his vast knowledge of such things that the device, as Tierney puts it, "could have been triggered from anywhere in Gibraltar, or even from Spain." Dr Michael Scott was called on in this inquest, and told The Maltese Double Cross:

"Particularly my experience in the Gibraltar case, one thing that struck me then at the time, very strongly - the British government employs hundreds of people, extraordinarily well qualified, in the areas of radio communications and electronics. Alan Feraday is not qualified, yet they use him? I mean, I have to ask the question why?"

Leppard noted how Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher took an interest in Feraday following this favourable inquest. "Clearly grateful for his efforts, [she] arranged that he be awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1988 New Year’s honours list."[30] Tierney reports that this was in June 1989, for "the Queen's Birthday honours".

Lockerbie bombing

Pan Am Flight 103 was sabotaged over Lockerbie, Scotland on 21 December 1988 killing all 259 passengers and crew, and a further 11 fatalities in the town of Lockerbie. Following a criminal investigation carried out by the Scottish police and the FBI, two Libyans were indicted for the crime in November 1991 on the basis of a tiny piece of timer circuit board which was alleged to have been found in the wreckage and which was identified by Alan Feraday, Dr Thomas Hayes and Thomas Thurman as having come from a MEBO MST-13 timer that had been sold to Libya. Both Alan Feraday and his RARDE colleague, Dr Thomas Hayes, gave expert witness evidence at the Lockerbie trial in 2000. Feraday testified that Pan Am Flight 103 was brought down on 21 December 1988 by a suitcase bomb triggered by an electronic timer made by the Swiss firm MEBO.[31] From a piece of charred clothing allegedly found at the scene of the crash in January 1989, Hayes teased out a tiny piece of timer circuit board in May 1989. The timer fragment was photographed at RARDE but was not tested for explosive residues. Feraday took the timer fragment to the FBI laboratory in the United States where Thomas Thurman was able to confirm that it had come from the MEBO MST-13 timer, twenty of which had been supplied to Libya.

Feraday's evidence

Allen Feraday, one of the Crown's key forensic witnesses completed his Lockerbie evidence today (15 June 2000).

- In his evidence in chief ('Joint Forensic Report' compiled with Dr Thomas Hayes), he stated that the explosion, which destroyed Pan Am Flight 103 and killed 270 people, exploded 25 inches inside the fuselage. He went to say that he had pinpointed the precise location of the blast after a detailed study of the damage suffered by all of the cases in the same luggage container as the bomb.

- Feraday went on to describe that he found at least 13 items of clothing and parts of an umbrella that were inside the Samsonite case at the time of detonation. It was on the second layer of luggage, resting in the angled container overhang - roughly parallel to the fuselage - or leaning upright, propped against another luggage stack.

- During cross-examination by Richard Keen QC, Feraday was challenged on whether the bomb could have been in any other position than set out in his forensic conclusions, Feraday replied:

- "I can't think of any other position." He went on: "I am not saying there isn't any other position, I just can't find it myself."

- Later Feraday was asked about an earlier case in which he had testified, Regina v Berry. Feraday's evidence was the single most important part of the prosecution's case against John Berry. The Court of Appeal rejected his "expert" evidence and Lord Chief Justice Taylor described Feraday's testimony at the trial as being "dogmatic". This questioning went not only to the witness's competency as an expert but also examined whether his professional opinion had changed from the time of the trial in the Berry case and the appeal.

- Feraday said he stood by his evidence at the Berry trial.

- Richard Keen QC asked him if he recalled a report he sent to John Orr, who at the time was heading the Police investigation at Lockerbie. The report is startlingly different from that reported to the court this week.

- Feraday stated in the first report that he was:

- "completely satisfied that the Lockerbie bomb had been contained inside a white Toshiba RT 8016 or 8026 radio-cassette player", and not, as he now testifies, inside a black Toshiba RT SF 16 model.

- Feraday was then challenged on his own handwritten notes and on whether they were taken contemporaneously or later. In some cases the official police log suggested that some pieces of evidence were not in Feraday’s possession when he claimed to have examined them and some were even logged as having been destroyed or returned to their owners prior to his examination having taken place.

- Keen also asked Feraday to state his qualifications. Feraday replied a "Higher National Certificate".

Commentary by Ian Ferguson:

- Undoubtedly Allen Feraday was an important witness for the Crown. His "dogmatic" approach in a number of cases is one of the hallmarks of his evidence. He is without doubt an expert at giving evidence, having done so often.

- His evidence today under cross-examination though highlighted discrepancies in his note taking and raised again the issue of the accuracy of the police logs. Testimony, by police officers, early on in the trial showed that the logging of items was not as accurate as they claimed.

- A few other issues arose today's testimony, regarding the placement of the bomb suitcase and Feraday's earlier report regarding the "white Toshiba." According to Feraday, he identified at least 13 items said to be from the Brown Samsonite suitcase, alleged to have contained the bomb. He pinpoints the location of the case down to the last centimetre, on the second layer of bags. Immediately below where Feraday claims the bomb went off, investigators identified a Grey Presikhaaf suitcase (belonging to UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson). In the early stages of the investigation, Bernt Carlsson's suitcase was seen as the more likely bomb case. Police sources at the time said that this case was cleared of being the suspect case on November 23rd 1989.

- To date not one item from the contents of Bernt Carlsson's Presikhaaf have been found. If there is a scientific reason why nothing has been found from this case, situated below the bomb case then it has not yet been explained in court. To a layperson it seems odd that the case adjacent to a bomb case should have no contents remaining, but from the bomb case itself we have an array of items. So what happened to the contents of Bernt Carlsson's Presikhaaf?

- In his evidence under questioning from Keen, Feraday dismisses the entire Court of Appeal in the John Berry case choosing instead to stick by his discredited evidence given at that trial. His obvious scant regard for the Courts of Appeal coupled with his dogmatic approach to stick to his story must have deserted him when he appears to so willingly change his earlier report to the Police from being:

- "completely satisfied that the Lockerbie bomb had been contained inside a white Toshiba RT 8016 or 8026 radio-cassette player" to as he now testifies, "inside a black Toshiba RT SF 16 model."

- Perhaps Lord Chief Justice Taylor consulted the Concise Oxford dictionary before describing Feraday's evidence in the Berry case. It lists his description of Feraday's evidence like this:

- "Dogmatic: adj. inclined to impose dogma; firmly asserting personal opinions as true. Origin: Dogma; a principle or set of principles laid down by an authority as incontrovertible."

- Any one familiar with Allen Feraday's testimony in previous trials and in the Courts of Appeal will know that incontrovertible is not always an apt description of his evidence.

More on previous Feraday trials soon (see above).[32]

Conviction

The clothing and the timer fragment led to the conviction of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi at the trial, and to his sentence of 27 years' imprisonment in Scotland. Megrahi's appeal against conviction was rejected in 2002 but he applied in 2003 to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) to review the case.[33]

Miscarriage of justice

On 28 June 2007, the SCCRC referred Megrahi's case back for another appeal on the basis that he may have suffered a miscarriage of justice.[34] The second appeal started at the High Court of Justiciary on 28 April 2009.[35] A documentary film Lockerbie Revisited, which was broadcast on Dutch television on 27 April 2009, focused on the MEBO timer fragment evidence and the role of Alan Feraday and the FBI's Thomas Thurman in its identification. Megrahi dropped the second appeal a few days before being granted compassionate release from prison on 20 August 2009, and returning to Libya.[36] Scotland's chief Lockerbie investigator, former Detective Chief Superintendent Stuart Henderson, was highly critical of the decision to release Megrahi.

Feraday's failure

On 7 March 2012, The Herald reported that in Megrahi's official biography by John Ashton there was new evidence showing the fragment of circuit board found at Lockerbie was 100% covered in tin and did not match those in the timers sent to Libya. It also alleged the Crown's forensic expert at trial, Allen Feraday, was aware of the disparity but failed to disclose it:

"Documents from the Ministry of Defence Royal Armaments Research and Development Establishment, disclosed by the Crown just before Megrahi's appeal was dropped, revealed contradictory notes from Mr Feraday saying the coating was "pure tin" and then "70/30 Sn/Pb" (70% tin and 30% lead)."

On 20 May 2012, Megrahi died of prostate cancer. His relatives and some Lockerbie victims' relatives are reported to be considering reopening Megrahi's appeal against conviction for the Lockerbie bombing.[37]

Damned with SCCRC's faint praise

In response to an application made in 1993 by lawyers representing Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the SCCRC published its report on 28 June 2007 granting Megrahi a second appeal against his conviction for the Lockerbie bombing. The following extract of the SCCRC report (Chapter 8, pages 163-173) deals with the previous cases involving 'expert witness' Allen Feraday, and damns him with "faint praise":

8.63 In May 2005 MacKechnie and Associates informed the Commission of an impending decision of the English Court of Appeal in the case of Hassan Assali, whose conviction in May 1985 under the Explosive Substances Act 1883 had been based primarily upon the evidence of Allen Feraday. Mr Assali’s case had been referred to the Court of Appeal by the Criminal Cases Review Commission ("the English Commission").

8.64 In the course of June and July 2005 MacKechnie and Associates provided the Commission with various papers analysing Mr Assali’s case and two others, R v Berry and R v McNamee, in which Mr Feraday had given evidence and in which the Court of Appeal had subsequently set aside the convictions. A paper addressing Mr Feraday’s involvement in the inquest into the shooting of three members of the IRA in Gibraltar was also provided. It appears that these papers had been prepared by [[John Ashton]], an investigative journalist employed by MacKechnie and Associates. Copies are contained in the appendix.

8.65 The Commission also obtained a number of documents from Mr Assali’s solicitors in London, including a copy of the English Commission’s statement of reasons and the report by Major Lewis and others upon which the referral to the Court of Appeal was based. On 19 July 2005 the Court of Appeal quashed Mr Assali’s conviction, the Crown not having opposed the appeal. The Commission obtained a copy of the court’s opinion, which is included in the appendix.

8.66 In the following months a number of television and newspapers reports referred to the decision in Assali and the two previous cases in which convictions based on Mr Feraday’s evidence had been quashed. There was much speculation on the impact these cases would have on the applicant’s case, given that he too was convicted at least partly on the basis of expert testimony by Mr Feraday.

Summaries of the cases and submissions

8.67 Before addressing the submissions it is appropriate to outline the circumstances of the three cases to which MacKechnie and Associates referred. The nature of Mr Feraday’s evidence in the various proceedings and the criticisms of that evidence in the submissions often involved technical matters which for present purposes it is unnecessary to address in great detail.

R v McNamee

8.68 On 27 October 1987 Gilbert "Danny" McNamee was convicted of conspiracy to cause explosions. His case was referred to the Court of Appeal by the English Commission and the conviction was quashed on 17 December 1998. The court’s opinion is reported at R v McNamee 1998 WL 1751094.

8.69 Mr McNamee was alleged to have been responsible for designing circuit boards for use by the IRA in explosive devices. He accepted that he worked on circuit boards for games machines at premises where the IRA made explosive devices but his position was that he had not known the premises were used for terrorist purposes.

8.70 A significant aspect of the evidence against Mr McNamee consisted of what were said to be his finger and thumb prints. They were recovered from three separate finds made by the British authorities, namely an explosive device and two caches of arms which included circuit boards. At appeal, expert evidence was heard which cast some doubt upon the identification of a thumbprint impression found on the explosive device, and the Court of Appeal held that they could not say the jury would necessarily have accepted that the print was readable had they heard this evidence at trial. The Court also considered significant the failure to disclose to the defence reports by an anti-terrorism police officer in which he named known terrorists, not Mr McNamee, as responsible for the majority of the circuit boards found in the arms caches referred to at the trial.

8.71 Mr Feraday’s evidence at the trial was that the tracking pattern on fragments of circuit board found in a bomb which exploded in Hyde Park in 1983 matched the tracking pattern on circuit boards in one of the caches on which, according to other evidence, Mr McNamee’s fingerprint had been found. Mr Feraday’s conclusion was that both circuit boards came from the same master artwork. Other experts at trial agreed with that conclusion, which therefore linked Mr McNamee to the Hyde Park bomb. The Crown invited the inference that he was responsible for the master artwork of these circuit boards. According to the trial judge’s summing up, Mr Feraday also testified that the tracking pattern on the circuit boards was especially devised for bombs, but another expert disagreed and stated that the pattern was originally devised for some other, innocent purpose.

8.72 At appeal, evidence was heard from a different expert, Dr Michael Scott, who also indicated that the circuit boards were originally for an innocent purpose. More significantly, he testified that whereas the tracking pattern on the Hyde Park fragments and the circuit boards in the arms cache on which Mr McNamee’s fingerprints were found did indeed match each other, the same pattern also matched various other circuit boards found in other arms caches. These included some found in Dublin and Northern Ireland which were not referred to at trial. Evidence indicated that other terrorists, not Mr McNamee, were responsible for making those circuit boards. As such, the similarity spoken to at trial could no longer be said to stand alone like a fingerprint, as had been emphasised by the Crown at trial on the basis of Mr Feraday’s evidence. In light of this new evidence and the undisclosed reports referred to above, the Court of Appeal concluded that it could no longer be inferred that Mr McNamee had been responsible for the master artwork of the circuit boards, as the Crown had alleged at trial.

R v Berry

8.73 John Berry was convicted on 24 May 1983 of an offence under section 4 of the Explosive Substances Act 1883, namely the making of a number of electronic timers in such circumstances as gave rise to a reasonable suspicion that they were not made for a lawful object. After a reference by the Secretary of State for the Home Department, the Court of Appeal quashed the conviction on 28 September 1993. The decision is reported at R v Berry (No.3) [1995] 1 WLR 7.

8.74 At the trial the Crown had alleged that the timers were designed and intended for use by terrorists to construct time bombs but Mr Berry claimed they had been supplied to the Syrian government and that they had numerous uses including for landing lights.

8.75 Of the four grounds argued before the Court of Appeal, the most relevant to Mr Feraday’s involvement in the trial was that relating to fresh evidence. It was agreed that Mr Feraday’s evidence had effectively been unchallenged at trial, as the only defence expert had accepted that he lacked experience in terrorist weaponry. It was Mr Feraday’s testimony that the timers made by Mr Berry could have been designed only for use by terrorists to cause explosions and as such it was critical to the conviction. He excluded non-explosive uses such as surveillance and lighting and suggested that legitimate armies would not use such timers because of the lack of an inbuilt safety device. However, the Court of Appeal heard fresh evidence from four experts, including Major Lewis and Dr Michael Scott, and stated that each of them disagreed with Mr Feraday’s "extremely dogmatic conclusion" about the timers, which they each felt were timers and nothing more, and which could be put to a variety of uses. In particular, whereas the absence of an inbuilt safety device in the timers might exclude their use by Western armies, the same could not be said of armies in the Middle East. Accordingly the verdict could not be considered safe.

R v Assali

8.76 As indicated, the Commission obtained a number of papers in relation to Mr Assali’s case. The case mirrors that of John Berry, in that Mr Assali was convicted under the Explosive Substances Act 1883 as a result of timers he produced, which in evidence Mr Feraday said had been specifically designed for terrorist use and which he could not contemplate being used other than in bombs. The English Commission referred the case to the Court of Appeal on the basis of an expert report by Major Lewis and others in which Mr Feraday’s conclusions were challenged and it was submitted that in fact the design of the timer was not suited for use in IEDs e.g. it was designed for repeated use and was difficult to set.

8.77 In June 2005 the Crown submitted a document to the Court of Appeal indicating that it would not resist Mr Assali’s appeal. It stated that, taking into account the new expert report, there was "a reasonable argument to suggest that" Mr Feraday’s evidence might well have been "open to reasonable doubt". The Crown emphasised that it was not conceding the correctness or otherwise of the fresh evidence and that its decision was made on the particular facts of the case and was not to be taken as having any wider significance. It stated that the decision was based on the perceived impact that the new material would be likely to have had on the jury and the inability to call evidence to contradict the new material. A copy of this document is included in the appendix.

8.78 In setting aside the conviction, the Court of Appeal referred to the decision in R v Berry and suggested that the implications for Mr Assali’s case were "obvious". It referred to the position adopted by the Crown but made no further findings, other than to state that on the basis of the expert evidence now available, the appeal had to be allowed.

Gibraltar inquest

8.79 In relation to the Gibraltar inquest, the following information was obtained from a paper submitted by MacKechnie and Associates and the relevant judgment of the European Court of Human Rights (McCann and Others v United Kingdom (1996) 21 EHRR 97).

8.80 In September 1988 an inquest was held by a Gibraltar coroner into the shooting there of three members of the IRA by British armed forces personnel. Mr Feraday provided a statement to the inquest and also gave evidence. The matter to which he spoke was whether, theoretically, a radio-controlled device such as was known to be used by the IRA could have detonated a bomb in a car the IRA members had left parked in one part of Gibraltar, by a transmission from the area in which they were shot dead. Mr Feraday’s position was that he could not rule out the possibility that a bomb could have been detonated, and another expert also gave evidence about trials which had been conducted in which some signals could be received between the relevant places. Dr Michael Scott, however, gave evidence that based on trials he had conducted his professional opinion was that a bomb could not be detonated in such circumstances.

8.81 The ruling of the inquest was that the killings had been lawful. In support of the subsequent application to the European Court of Human Rights Dr Scott challenged Mr Feraday’s evidence and reiterated his own conclusions. The decision of the European Commission on Human Rights was that there was no violation of the Convention and, according to the paper submitted by MacKechnie and Associates, that it was not unjustified for the British authorities to have assumed that detonation was possible. The European Court, however, found there to be a violation of article 2 of the Convention on the basis of a lack of care and control on the part of the British authorities in carrying out the operation. The question of whether or not detonation would have been possible was described in its judgment (in particular paragraph 112 et seq) but did not play a significant part in its findings.

Summary of submissions

8.82 The various papers submitted by MacKechnie and Associates contain long and detailed analyses of and comparisons between Mr Feraday’s evidence in the proceedings summarised above and make a number of criticisms of him. Again, for the present purposes it is necessary only to summarise briefly a number of those submissions.

8.83 In relation to the Gibraltar inquest reference is made in the submissions to Mr Feraday’s lack of qualifications and it is alleged that he made a number of technical errors in his description of radio wave propagation. Reliance is placed upon Dr Scott’s opinions which contradict much of Mr Feraday’s account. It is pointed out that despite his experience in examining terrorist devices and their remains, Mr Feraday had no specialist knowledge in radio communications and, in contrast to Dr Scott, failed to undertake any tests with the relevant equipment in Gibraltar. According to the report, rather than admit ignorance, Mr Feraday made factually inaccurate claims and also claimed that the "vastly more qualified" Dr Scott was wrong in his conclusions. Dr Scott’s view was that Mr Feraday’s conduct was "quite astonishing".

8.84 As regards Berry and Assali, the papers submitted to the Commission (which pre-date the Court of Appeal’s decision in Assali) again make detailed criticisms of Mr Feraday’s conclusions and refer to contradictions which are apparent between his accounts in each case. The point is made that in each case Mr Feraday said the timer in question was specifically designed for terrorist purposes, yet the actual timers were quite different to each other in a number of respects including their size and the length of time for which they could be set.

8.85 Moreover, it is submitted that in Berry Mr Feraday testified that timers with inbuilt safety devices were not normally used by terrorists, who preferred to use some external visual safety mechanism, like a warning bulb. It is submitted that the absence of an inbuilt safety device in the timers produced by Mr Berry was regarded by Mr Feraday as an important factor in establishing its terrorist purpose. It is suggested that Mr Feraday further testified that he had never come across terrorists using timers which had inbuilt safety devices and that they would instead apply their own safety circuit, yet the Assali, IRA and MST-13 timers all had inbuilt safety mechanisms, such as an LED which would illuminate when the switch was closed. In Berry Dr Scott’s opinion was that terrorists would always require a built in safety device, but Major Lewis disagreed and suggested that although such a device was evidence that the timer was to be used for a hazardous purpose, terrorists generally chose simple, general purpose timers which lacked such a circuit, because they could be acquired innocently. It is pointed out that in Assali Mr Feraday suggested that the LED on the timer would act as an extra safety device in the event of a failure in the terrorist’s own safety apparatus, such as an external circuit and bulb, which they tended to use because they did not trust inbuilt devices.

8.86 A further matter raised in relation to Berry is Dr Scott’s opinion that Mr Feraday’s testimony about the amount of current the timer in question could handle was "utterly dishonest". As regards Assali, reference is made to various aspects of Mr Feraday’s testimony which were contradicted in the subsequent expert reports, such as Mr Feraday’s assertion that the repeat mode on the timer was not an intentional part of its design, a fact refuted by the other experts. It is suggested that in Assali Mr Feraday was every bit as "dogmatic" as he had been in Berry, and the suggestion is made that Mr Feraday may not have been competent, given that he failed to identify various features of the timers which were referred to by the other experts. The submission is also made that Mr Feraday gave evidence in bad faith, particularly in light of the contrasting positions he adopted in Berry and Assali as regards the use by terrorists of timers with inbuilt safety devices.

8.87 Some specific comparisons with the applicant’s case are also made in the papers. With regard to Mr Feraday’s testimony in Berry that all terrorists like to have an external safety feature in their IEDs, the point is made that the devices recovered in the Autumn Leaves operation did not contain such safety features, and neither did Mr Feraday’s reconstruction of the device used to destroy Pan Am 103. It is suggested that the absence of an external safety circuit in Mr Feraday’s reconstruction is implicit acceptance that the terrorists would have considered the MST-13’s inbuilt warning light sufficient.

8.88 As regards McNamee, the submissions make reference to various aspects of Dr Scott’s opinions in which the evidence of Mr Feraday is criticised. Specific mention is also made of the fact that, as in Assali and Berry, Mr Feraday concluded that the circuit boards in question were designed for terrorist bombs, a fact with which another expert at trial, and Dr Scott at appeal, disagreed.

Mr Feraday’s position at interview

8.89 At interview with the Commission’s enquiry team on 7 March 2006 Mr Feraday was asked about the cases of Berry, Assali and McNamee. His statement is contained in the appendix of Commission interviews. In brief, his view was that there was no connection between those cases and that of the applicant. He maintained that his opinion in Berry had been correct, and he disputed a number of the allegations made about his testimony in that case. He felt aggrieved at the Crown’s approach to the appeals in Berry and Assali and he produced photographs which he suggested proved that the Berry timers had been used in terrorist devices but which the Crown failed to rely upon at either appeal. He was of the view that his evidence in McNamee was irrelevant to the Court of Appeal’s decision that the conviction in that case was unsafe.

Consideration

8.90 The Commission notes that at the applicant’s trial Mr Feraday spoke to a number of critical issues including the identification of the Toshiba RT-SF16 radio cassette recorder as the device which contained the explosives, the identification of the fragment PT/35(b) as having come from an MST-13 timer which initiated the explosion and the reconstruction of the IED and its positioning within the baggage container. Accordingly, evidence which raises significant doubts about the credibility or reliability of Mr Feraday’s conclusions in the applicant’s case would potentially undermine the basis of the court’s verdict. On the other hand, as was acknowledged by MacKechnie and Associates in the letter of 14 June 2005 which enclosed the submissions on this point, "it does not follow that, even if Mr Feraday’s evidence in other cases was misguided, overstated or even false, that his evidence in the Lockerbie case should be open to question for that reason alone."

8.91 As indicated, prior to trial the applicant’s defence team instructed forensic experts from FSANI to examine a number of areas of the case. It is clear from their final report (DP 21) and from file notes of meetings that the defence experts agreed with the majority of Mr Feraday’s conclusions. Crucially, in respect of the timer fragment the experts were satisfied that it had suffered damage consistent with it having been closely associated with an explosion (DP 21, p 6) and that it had come from an MST-13 timer (as described in the relevant section above).

8.92 Moreover, where Mr Feraday testified about matters with which the defence experts disagreed, such as the possible positioning of the primary suitcase in the baggage container, Mr Feraday was cross-examined about them in some detail (21/3278 et seq).

8.93 In these circumstances, and having considered the matters raised under this ground of review, the Commission does not believe that the information about previous cases involving Mr Feraday undermines his conclusions at the applicant’s trial. As regards the Gibraltar inquest, the issues in question were quite different, relating as they did to the possible detonation of explosives by radio transmission. Although Dr Scott clearly disagreed strongly with Mr Feraday’s evidence at the inquest, another expert at least partly supported Mr Feraday’s position and there was no judicial criticism of him in any of the subsequent proceedings. Nor was there any direct judicial criticism of Mr Feraday in McNamee. His conclusion that the Hyde Park fragments matched a circuit board in one of the arms caches was not in itself disputed, and was spoken to by another expert at the trial. It was the revelation that those fragments also matched a number of other circuit boards, some of which had not been led at trial, which contributed to doubts about the safety of the conviction. There was also a suggestion that the undisclosed police report had been provided to RARDE but it was not suggested that Mr Feraday himself had had access to that report or had failed to disclose it.

8.94 McNamee reflects Berry and Assali to the extent that Mr Feraday concluded in all three cases that the items he examined were specifically designed for use in terrorist devices, conclusions which were challenged by fresh expert evidence at appeal and which in the latter two cases directly led to the convictions being overturned. However, in the applicant’s case Mr Feraday did not assert that MST-13 timers were designed specifically for use in terrorist devices. On the contrary, the RARDE report describes the timer as "specifically designed and constructed as a versatile programmable electronic timer capable of firing any electronic detonator connected to its terminal block after a preset period of delay" (CP 181, section 7.1.1).

8.95 Given the lack of any direct correlation between Mr Feraday’s findings in the applicant’s trial and his opinions in the previous cases, what remains is a general criticism that he may in the past have expressed unjustifiably definite (and incriminating) conclusions about matters with which more technically qualified experts have disagreed. However, as stated above, his conclusions in the applicant’s case, including the conclusion that PT/35(b) came from an MST-13 timer that initiated the explosion, were largely supported by the defence experts.

8.96 It is also important to note that, with the exception of the Court of Appeal’s decision in Assali, all the cases in question were concluded prior to the applicant’s trial. Indeed, it is clear from a number of papers contained in the McGrigors electronic files that the defence was well aware of Mr Feraday’s role in all those proceedings (including Assali, which at the time was under review by the English Commission). Accordingly, little of what is raised in the papers submitted to the Commission constitutes new information or fresh evidence. Indeed, at trial counsel for the co-accused cross examined Mr Feraday about the events in Berry, including the Court of Appeal’s description of his opinion in that case as "extremely dogmatic". Counsel also referred Mr Feraday to the passage in the Court of Appeal’s opinion in Berry in which it was suggested that he had "partially conceded" that his conclusions at trial had been "open to doubt at the very least" (21/3270 et seq).

8.97 Accordingly it cannot be said that the trial court in the applicant’s case reached its verdict in ignorance of the judicial criticisms to which Mr Feraday had been subjected. Given that at the time there was an absence of similar criticism in the other cases, the Commission does not believe that there would have been much value to the defence in also raising those cases during cross-examination.

8.98 The Commission acknowledges that the position now is somewhat different as regards Assali, the Court of Appeal having quashed the conviction under reference to Berry. Had that outcome occurred prior to the applicant’s trial it is possible that counsel might have referred to Assali as well as Berry in an attempt to cast further doubt upon Mr Feraday’s evidence. However, in light of its conclusions above, the Commission is not persuaded that such a reference to Assali would have added anything of significance. In particular, the issues in that case and in the other cases were different in nature to those about which Mr Feraday gave evidence at the applicant’s trial.

Conclusion in relation to ground 4

8.99 In light of the findings here and in the rest of this section of the statement of reasons, the Commission does not believe that Mr Feraday’s involvement in the previous cases referred to above may have given rise to miscarriage of justice in the applicant’s case.[38]

Personal life

Alan Feraday is married to former teacher Gillian, who is eleven years his junior, and lives in Rochester, Kent.[39] Their daughter Caroline is a radio DJ and television broadcaster, who married media lawyer Mark Lewis on 9 March 2013.[40]

Called a liar

In October 2013, Alan Feraday was called a liar by Steven Raeburn, editor of Scots Law magazine The Firm, in a devastating criticism of Morag Kerr's book entitled "Adequately Explained by Stupidity?" about the Lockerbie bombing:

- "Dangerous, suspicious Government-fed propaganda, based on the discredited Feraday/Hayes lies. Beware."[41]

Tweet Twat

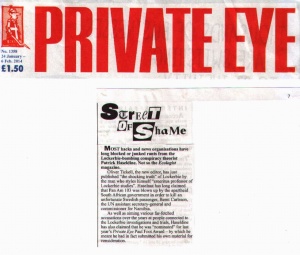

On 4 February 2014, Caroline Feraday (Mrs Mark Lewis) cited an article in the latest issue of Private Eye magazine about Patrick Haseldine's nomination for the 2013 Paul Foot Award, an extract of which reads:

- "As well as aiming various far-fetched accusations over the years at people connected to the Lockerbie investigations and trials, Haseldine has also claimed that he was 'nominated' for last year’s Private Eye Paul Foot Award – by which he meant he had in fact submitted his own material for consideration."[42]

Caroline Feraday then tweeted to Patrick Haseldine (@BerntCarlsson), as follows:

- Have you nominated yourself for 'Twat of the Year' too?[43]

Mark Lewis, having favorited his wife's tweet and retweeted it to his 3,481 Twitter followers, thoughtfully added his own tweet:

- Lockerbie: Private Eye rumbles "Haselnut" and The Ecologist:

- Why tweet as @BerntCarlsson when #Haselnut would be apt?[44]

In response to Mr and Mrs Lewis, Patrick Haseldine tweeted:

- "#TwatOfTheYear" is preferable to "#OdiousBombExpert" awarded to your dad #AlanFeraday (https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Alan_Feraday) #Lockerbie [45]

- @MarkLewisLawyer Nice nickname @BerntCarlsson remains the highest profile #Lockerbie victim (https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Alan_Feraday#Tweet_Twat) failed by #AlanFeraday[46]

Sir Alan Feraday?

On 6 February 2014, Professor Francis Boyle, author of "Destroying Libya and World Order", emailed former diplomat Patrick Haseldine with the outrageous suggestion that Alan Feraday be awarded a knighthood for services to British justice!

See also

- Lockerbie Official Narrative

- Cameron's Report on Lockerbie Forensic Evidence

- The Framing of al-Megrahi

- The How, Why and Who of Pan Am Flight 103

External links

- "Police investigations of 'politically sensitive' or high profile crimes" Report on the Lockerbie investigation by former Lord Advocate Colin Boyd

- "The Iron Lady's Revenge"

References

- ↑ "The Forensic Files (part 1)"

- ↑ "'Gibraltar', a New Play: a Look at 'Death On The Rock' 25 Years On"

- ↑ Appeal Judgment in the case of John Berry, 28 September 1993

- ↑ "Evidence that casts doubt on who brought down Flight 103"

- ↑ "Introducing Allen Feraday"

- ↑ "June 13th 2000 Testimony of Allen Feraday"

- ↑ "The Framing of al-Megrahi"

- ↑ "PQ on the Caddy Inquiry" (1996-12-09)

- ↑ "Caddy Inquiry: Forensic Explosives Laboratory"

- ↑ "Commentary on Feraday"

- ↑ Dr Michael Scott report on the McNamee case

- ↑ "Alan Feraday and the Evidence of the Lockerbie Trial"

- ↑ Appeal Judgment in the case of Gilbert McNamee

- ↑ "McNamee's 11-year campaign for justice "

- ↑ "IRA Hyde Park bomb: John Downey denies murder"

- ↑ "John Anthony Downey in court over 1982 IRA Hyde Park bombing"

- ↑ "REVEALED: THE TOP SINN FEIN MEMBER CHARGED OVER IRA HYDE PARK BOMB MURDERS"

- ↑ "IRA bomb accused John Downey granted bail"

- ↑ Gareth Peirce's critique of Alan Feraday OBE

- ↑ "Regina v Berry"

- ↑ Report by Dr John Wyatt for the Appeal of John Berry

- ↑ Appeal Judgment in the case of John Berry, 28 September 1993

- ↑ "Alan Feraday and the evidence of the Lockerbie trial" Ludwig de Braekeleer, Canada Free Press Retrieved on 2009-05-14

- ↑ "Bomb expert links hotel device to Glasgow cache"

- ↑ "Outrage as Brighton bomber freed"

- ↑ "Commission refers conviction of Mr Hassan Assali to Court of Appeal" (2003-04-19)

- ↑ "'Doubts' over Lockerbie evidence"

- ↑ "Trial doubts may free Lockerbie Libyan"

- ↑ "IRA gang shot dead in Gibraltar"

- ↑ Leppard, David. "On the Trail of Terror: The Inside Story of the Lockerbie Investigation" London, Jonathan Cape. 1991. 221 pages.

- ↑ "Lockerbie bomb 'in suitcase'" BBC News (2000-06-15)

- ↑ "Feraday's Evidence - The Final Day"

- ↑ "Lockerbie terror bomber's conviction thrown into doubt" Edinburgh Evening News, Lucy Christie (2005-08-19)

- ↑ "Re-Opening the Lockerbie Tragedy" TIME Laura Blue

- ↑ "Lockerbie bomber Megrahi may be allowed home" Jason Allardyce; Mark Macaskill (2009-05-10)

- ↑ "Lockerbie bomber freed from jail"

- ↑ "Lockerbie bomber Abdelbaset al-Megrahi reported dead in Libya"

- ↑ "SCCRC Statement of Reasons (Chapter 8, pages 163-173, paras 8.63-8.99)"

- ↑ "Caroline Feraday and mum Gillian"

- ↑ "DJ Caroline Feraday's brief encounter"

- ↑ @MrStevenRaeburn

- ↑ "Private Eye rumbles 'Haselnut' and The Ecologist"

- ↑ "Have you nominated yourself for 'Twat of the Year' too?"

- ↑ "Why tweet as @BerntCarlsson when #Haselnut would be apt?"

- ↑ "Odious Bomb Expert"

- ↑ "Highest profile Pan Am Flight 103 victim"