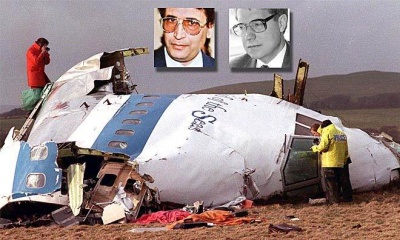

The How, Why and Who of Pan Am Flight 103

|

The how, why and who of Pan Am Flight 103 is an attempt to summarise the story of Pan Am Flight 103 which on 21 December 1988 exploded killing all 259 passengers and crew, and eleven people in the town of Lockerbie, Scotland.[1] Like the rest of the site, it is a work in progress, not necessarily to be regarded as definitive. Supporting discussion is particularly welcome on the this article's discussion page. |

Contents

How Pan Am Flight 103 was sabotaged

The sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103 on 21 December 1988 was done by putting a Samsonite hardshell suitcase containing a barometrically-triggered bomb into baggage tin AVE4041, which was the eighth and final baggage container loaded onto the Boeing jumbo jet at London's Heathrow airport.

Evidence of Barry Walker (RHKP)

According to Lockerbie detective Barry Walker (formerly of the Royal Hong Kong Police):

- "The most important witness in the Lockerbie case was a Heathrow baggage handler, John Bedford, a loader/driver employed by Pan Am. Yet from the start his evidence was discounted or ignored, deemed to be of no relevance at all. On the afternoon of the 21 December 1988, Bedford was working at the Interline Baggage Shed a structure where Interline bags that arrived from other flights were brought and fed into the shed on a conveyor belt that extruded from the building. Here the bags were x-rayed and placed into luggage containers. Bedford had set aside luggage container AVE4041 for flight Pan Am 103. Bedford placed four or five suitcases, upright on their spines to the back of the luggage container then left the area to speak with his supervisor."[2]

Evidence of Dr Morag Kerr

Dr Morag Kerr, deputy secretary of the Justice for Megrahi campaign group, conducted a study into the Lockerbie luggage, publishing her findings in September 2012:[3]

- "Maid of the Seas carried eight containers of passenger luggage. Seven of these were filled with suitcases checked in at Heathrow, and sorted into the containers in the large and busy baggage build-up shed at the airport. The eighth was a container AVE4041 that had been partially loaded in the Interline Baggage Shed, and filled outside on the tarmac, taking luggage directly from the Pan Am feeder flight (Pan Am 103A) which had arrived late from Frankfurt with only 20 minutes to spare. That container was sent straight to the adjacent stand where the transatlantic flight (Pan Am 103) was preparing to depart, without entering the terminal buildings.

- On Christmas Eve 1988, three days after the disaster, the first piece of blast-damaged container framework was brought in from the fields to the east of Lockerbie. This was the first positive indication that the crash had indeed been caused by an explosion, as many had suspected from the outset, and it also indicated that the explosion was associated with passenger hold luggage rather than cabin baggage or cargo.

- Baggage handler John Bedford’s police statements reveal that when he set up the container to receive luggage for Pan Am 103, there were already two suitcases sitting beside the x-ray machine. He duly placed the cases in the container, upright with the handle(s) up, at the back, to the extreme left of the flat part of the floor. During the afternoon another four or five cases arrived, which he added to the line he had begun, working from left to right. At about quarter past four, as all was quiet, he went off for a tea break with his supervisor Peter Walker.

- The only luggage which could possibly have arrived in the shed before Bedford set up the container just after two o’clock was Mr Carlsson’s single suitcase and Nicola Hall's suitcase. However, although Miss Hall was booked on Pan Am 103, her suitcase was sent to New York on Pan Am 101 which left at mid-day. Thus the "bomb bag", having been substituted for Nicola Hall's suitcase, must have been adjacent to Bernt Carlsson's grey Presikhaaf hardshell suitcase. Mr Carlsson’s case was the most severely damaged of the group, but even that was not presented in court as having sustained damage consistent with its having been underneath the bomb, and since it is known to have been placed immediately behind the bomb suitcase within a foot or so of the IED, it would have been expected to be severely damaged in any event."

Unlawful baggage switch

Nicola Jane Hall, aged 23 years, of Sandton, South Africa, was in seat 23K on Pan Am Flight 103 when the aircraft exploded over Lockerbie.

To get to London's Heathrow airport, Nicola Hall had travelled overnight from Johannesburg on South African Airways (SAA) Flight 234 with a high-powered apartheid regime delegation which included foreign minister Pik Botha, defence minister Magnus Malan and military intelligence chief General C J Van Tonder. Because SAA had been banned from flying direct to and landing in the United States (on account of the 1986 Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act) the South African party were all booked for onward travel by the US carrier Pan Am from London, Heathrow to JFK, New York.

After an eleven-hour flight, SA234 arrived at Heathrow at 07:20am. Pik Botha and his party were booked on Pan Am Flight 101 departing Heathrow at 11:00am to New York for the signing ceremony of the Namibia independence agreement at UN headquarters on the following day Thursday, 22 December 1988.

Although she was not in Pik Botha's official party, and was booked on the fatal evening flight Pan Am 103 departing Heathrow at 18:00pm, Nicola Hall's suitcase did not accompany her. It had been wrongly transferred at Heathrow to the morning flight Pan Am 101.

That South African Airways were involved in unlawfully switching baggage that day was confirmed by a Pan Am security officer, Michael Jones, at the Lockerbie fatal accident inquiry (FAI) in October 1990. Jones told the FAI a breach of aviation rules had been committed because the suitcase of South African passenger, Miss Nicola Hall, had been put on the earlier Pan Am 101 flight (with Pik Botha's delegation) whereas Miss Hall was booked – and died – on PA 103.[4]

Primary suitcase

At about 20:00pm (GMT) on 20 December 1988, when flight SA234 took off from Johannesburg airport, full details of the flight's passenger manifest were transmitted to South African Airways office in London. This was the cue for a team of Civil Co-operation Bureau operatives, led by the CCB's London-based director Eeben Barlow, to break through a security door at Terminal 3 of Heathrow airport leading to the Interline Baggage Shed from where flights would be loaded the following day. The CCB team then ingested the primary suitcase (or "bomb bag") through this security door and tagged it for loading on Pan Am Flight 103.[5] For baggage reconciliation purposes, this Samsonite hardshell primary suitcase would replace Nicola Hall's bag (which would be diverted to Pan Am Flight 101). Thus the "bomb bag" and Bernt Carlsson's grey Presikhaaf hardshell suitcase were the first two pieces of luggage placed in the AVE4041 baggage container by loader/driver John Bedford.

Heathrow security guard Ray Manly, who discovered that the padlock had been cut on security door CP2 leading to the Pan Am baggage area, told the Lockerbie appeal court at Camp Zeist in 2002:

- "I believe it would be possible for an unauthorised person to obtain tags for a particular Pan Am flight and then, having broken the CP2 lock, to have introduced a tagged bag into the baggage build up area."

Manly immediately reported the break-in to the police but was not interviewed by the Metropolitan Police until 31 January 1989. No mention of the Heathrow break-in was made at the 2000-2001 Lockerbie trial of the two Libyans Megrahi and Fhimah.[6]

Was this a PFLP-GC bomb?

Marwan Khreesat, a Jordanian double agent who infiltrated the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command (PFLP-GC), told FBI special agent Edward Marshman and forensic investigator Thomas Thurman in 1989 that he had built five barometrically triggered aircraft bombs when he was in Neuss, West Germany in October 1988. German BKA police intercepted four of these devices in November 1988 following the arrest of a PFLP-GC terrorist cell in Neuss. Khreesat said that the fifth bomb had been taken by a senior PFLP-GC agent named Abu Elias, who escaped arrest in Germany. Abu Elias is suspected of supplying the South African CCB with the bomb that brought down Pan Am Flight 103.[7]

Why Pan Am Flight 103 was sabotaged

The apartheid South African regime targeted Bernt Carlsson, Assistant-Secretary-General of the United Nations and UN Commissioner for Namibia, on Pan Am Flight 103, which was sabotaged over Lockerbie, Scotland on Wednesday, 21 December 1988. All 259 passengers and crew on the flight were killed as well as eleven people in the town of Lockerbie. Newspaper reports quickly identified Bernt Carlsson as the highest profile victim.

According to these reports, Bernt Carlsson was on his way to New York to attend the signing ceremony on 22 December 1988 at United Nations headquarters of an agreement granting independence to Namibia, which had been illegally occupied by apartheid South Africa for over twenty years. Following the UN Commissioner's death at Lockerbie, South African foreign minister Pik Botha went ahead and signed the agreement. However, instead of handing control of Namibia to the United Nations, Pik Botha put the apartheid regime's Administrator-General, Louis Pienaar, in charge.

No investigation by the Scottish Police, the CIA, the FBI or the United Nations has ever been conducted into this compelling circumstantial evidence of the targeting of Bernt Carlsson on Pan Am Flight 103, despite the branding of apartheid South Africa as a "terrorist state" during the 1988 US presidential election campaign.[8]

Carlsson's "secret meeting"

Jan-Olof Bengtsson is the political editor of Kvällsposten newspaper in Malmö, Sweden, and a renowned investigative journalist. Mr Bengtsson's most important work - although perhaps the least publicised - is his series of three articles in Sweden's iDAG newspaper on 12, 13 and 14 March 1990. Never published in the English language, the iDAG articles featured Sweden's UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson who was the most prominent victim of Pan Am Flight 103 which was sabotaged over Lockerbie, Scotland on 21 December 1988. Bengtsson alleged that Commissioner Carlsson's arm had been twisted by the diamond mining giant De Beers into making a stopover in London for a secret meeting and into joining the doomed flight, rather than taking as he had intended a Sabena flight direct from Brussels to New York:[9]

- "Bernt Carlsson, UN Commissioner for Namibia, had less than seven hours to live when at 11.06am on 21 December 1988 he arrived in London on flight BA 391.

- "Strictly speaking he was meant to fly directly from Brussels to New York in time for the historic signing of the Namibia Independence Agreement the day after. But Bernt Carlsson could not make it. He had a meeting. An important meeting with a 'pressuriser' from the South African diamond cartel, which was so secret that evidently not even Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, UN Secretary-General, knew anything about it. Here iDAG maps out the last 24 hours in the life of Bernt Carlsson.

- "The memorial service in the Folkets Hus in Stockholm on 11 January 1989 for Bernt Carlsson gathered most of our Heads of Government, representatives of the Namibia independence movement SWAPO and Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, the UN Secretary-General.

- "When he died in the Pan Am bombing, Bernt Carlsson was less than 24 hours away from the fulfilment of his dreams - the signing of the Namibia agreement in New York which would finally pave the way to a free and independent Namibia. This was supposed to be the climax of his career with the UN, a career that began in December 1986 when he was appointed Commissioner for Namibia. Bernt Carlsson had great support from SWAPO but much less so from South Africa because of that country's substantial economic interests in Namibia: an interest in gold, uranium but above all in diamonds.

- "Javier Pérez de Cuéllar in his speech at the memorial ceremony on a cold day in January last year [1989] described the last 24 hours in the life of Bernt Carlsson:

- 'Bernt Carlsson was returning to New York following an official visit to Brussels where he had spoken to a Committee within the European Parliament about the Namibia agreement,' Pérez de Cuéllar began. 'He stopped briefly in London to honour a long-standing invitation by a non-governmental organisation with interests in Namibia.'

- "Pérez de Cuéllar was wrong. True, Bernt Carlsson's trip to Brussels had been planned almost six months earlier. But his decision to return to New York via London was only made on 16 December 1988. The meeting in London was definitely not a long-standing invitation by Namibia sympathisers."

Call for independent inquiry

In September 2009, former Labour MEP Michael McGowan called for an urgent independent inquiry led by the United Nations into the Lockerbie disaster. McGowan wrote that he was personally affected by the crash:

- "As President of the Development Committee of the European Parliament, I had invited Bernt Carlsson, the Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations and UN Commissioner for Namibia, to call in at Brussels in December 1988. He was on his way back to the United States from Namibia and agreed to address members of the Development Committee, which he did. In Brussels, he spoke about his hopes for an independent Namibia and the end of apartheid in South Africa to a packed meeting of MEPs.

- "And afterwards he confirmed his acceptance to visit Leeds the following year to give the 1989 Peace Lecture in honour of Olof Palme, the former Swedish Prime Minister, who was murdered in Stockholm on February 28, 1986. He said how much he was looking forward to coming to Leeds to pay tribute to his fellow Swede with whom he had worked closely as international secretary of the Social Democratic Party of Sweden, and also as a special adviser to Palme. Bernt Carlsson did not make that visit to Leeds in 1989. He was a passenger on Pan Am Flight 103 and he died when the plane was blown up over Lockerbie on December 21, 1988. He was a giant of diplomacy, gentle, quiet, but a tough negotiator. His death, like that of his friend and fellow Swede, Prime Minister Palme, who was murdered in the street in Stockholm returning with his wife from a night at the cinema, was the result of a terrorist act and remains a mystery.

- "A call by the British Government for an independent inquiry led by the United Nations to find out the truth about Pan Am Flight 103 is urgently required. We owe it to the families of the victims of Lockerbie and the international community to identify those responsible. That Bernt Carlsson was on that plane should be an extra incentive for the UN to take action in view of the fact that this impressive diplomat was dealing with some of the most sensitive and violent situations being perpetrated by the brutal apartheid regime in both South Africa and Namibia, besides his work in the Middle East. The best tribute to the lives and families of the 270 victims of Lockerbie, including Bernt Carlsson, and the most positive action for the international community to take against terrorism, is to launch an independent inquiry into this gross act of mass murder. Nothing less will suffice."[10]

Who sabotaged Pan Am Flight 103?

Twenty seven years before Pan Am Flight 103, United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld was en route to negotiate a cease-fire in the former Belgian Congo when his McDonnell Douglas DC-6 airliner crashed near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) on 18 September 1961. Hammarskjöld and fifteen others perished in the crash.

It is striking to note the points of similarity between the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and UN Assistant-Secretary-General Bernt Carlsson: both Swedes; both UN diplomats; both concerned with mineral-rich countries (Congo and Namibia); both operating in Cold War circumstances where the West sought to contain Soviet expansionism (especially in Central and Southern Africa).

Involvement of MI6, CIA and BOSS

On 19 August 1998, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), stated that recently uncovered letters had implicated the British MI6, the American CIA and South African BOSS intelligence services in Hammarskjöld's aircrash. The letters, headed "South African Institute for Maritime Research" (SAIMR) — said to be a front company for the South African military — include references to the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the British MI6 security service. The CIA last year (1997) opened its files on Cold War assassinations and admitted it ordered the murder of Patrice Lumumba, Congolese independence hero and pro-Soviet prime minister.[11]

In a meeting between MI6, special ops executive and the SAIMR, the following emerged from one document marked 'Top Secret':

- "It is felt that Hammarskjöld should be removed. I want his removal to be handled more efficiently than was Patrice."

Another letter headed "Operation Celeste" gave details of orders to plant explosives in the wheel bay of an aircraft primed to go off as the wheels were retracted on takeoff.[12]

Archbishop Tutu said that the TRC, whose mandate expired at the end of July 1998, was unable to investigate the veracity of the letters or the allegations that South African and/or Western intelligence agencies played a role in Hammarskjöld's aircrash. Tutu passed the letters to South African Justice Minister Dullah Omar.

The British Foreign Office suggested that the letters may have been created in the 1960s as Soviet misinformation or disinformation.[13]

Congo's huge mineral deposits

Swedish aid worker, Göran Björkdahl, who investigated Dag Hammarskjöld's death in the aircrash, said:

- "It's clear there were a lot of circumstances pointing to possible involvement by western powers. The motive was there – the threat to the west's interests in Congo's huge mineral deposits. And this was the time of black African liberation, and you had whites who were desperate to cling on. Dag Hammarskjöld was trying to stick to the UN charter and the rules of international law. I have the impression from his telegrams and his private letters that he was disgusted by the behaviour of the big powers."[14][15][16]

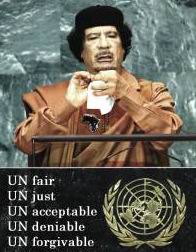

Gaddafi calls for UN investigation

On 16 September 2009, Patrick Haseldine wrote on Professor Black's blog:

- "Another option would be for the United Nations to launch an investigation that would command international co-operation", says The Sunday Herald. This interesting idea is not developed by the newspaper, however. I am reminded that the Libyan leader, Colonel Gaddafi, is scheduled to address the UN General Assembly in New York on 23 September 2009. Libya currently occupies one of the 15 seats on the UN Security Council, and with the Libyan former foreign minister, Ali Treki, about to become president of UNGA, it would be very surprising if Gaddafi did not use his UN speech to call for a 'United Nations Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing'.[17]

In fact, in his long, rambling speech to the 64th session of the United Nations General Assembly on 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi didn't even mention Pan Am Flight 103, but did call upon the Libyan president of UNGA, Ali Treki, to institute a UN investigation into the assassinations of Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, who was overthrown in 1960 and murdered the following year, and of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in 1961.[18]

Naming names

This WikiSpooks synthesis suggests that a set of CIA, MI6 and BOSS officials, together with other high level politicians were aware of (and even have encouraged) apartheid South Africa's plan to target Bernt Carlsson by sabotaging Pan Am Flight 103. Individuals directly responsible for the sabotage of Pan Am Flight 103 include:

- P. W. Botha (deceased),

- Pik Botha,

- Craig Williamson &

- Eeben Barlow

See also

References

- ↑ "Victims of Pan Am Flight 103"

- ↑ "Lockerbie: The Heathrow Evidence"

- ↑ "Heathrow baggage transfers and the Bedford suitcase"

- ↑ "Lockerbie Fatal Accident Inquiry"

- ↑ "Pan Am 103: South Africa Guilty"

- ↑ 'Break-in' before Lockerbie bombing

- ↑ "Lockerbie: Ayatollah's Vengeance Exacted by Botha's Regime"

- ↑ Dukakis Backers Agree Platform Will Call South Africa 'Terrorist'

- ↑ "Bernt Carlsson in a secret meeting with 'pressuriser' from the Diamond Cartel"

- ↑ "The best tribute to the 270 victims of Lockerbie is to find out the truth"

- ↑ "Notes for Media Briefing" by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Chairperson of the Truth And Reconciliation Commission, 19 August 1998

- ↑ "Letters Say Hammarskjöld Death Western Plot"

- ↑ "UN assassination plot denied"

- ↑ "Dag Hammarskjöld: evidence suggests UN chief's plane was shot down"

- ↑ "I have no doubt Dag Hammarskjöld's plane was brought down", Göran Björkdahl, The Guardian, 2011 Aug 17

- ↑ "Call for new inquiry following emergence of new evidence" The Guardian 2011 Sept 16

- ↑ "Patrick Haseldine writing on Professor Black's blog"

- ↑ "Gaddafi's address to UN General Assembly" 23 September 2009