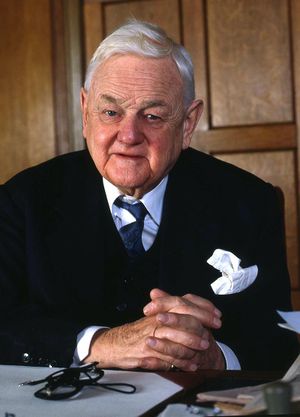

Quintin Hogg

(politician) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1907-10-09 London, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2001-10-12 (Age 94) London, United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | UK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Eton College, Christ Church (Oxford) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Natalie Sullivan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Conservative | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At time of Bilderberg, possible candidate for leadership of UK Conservative Party

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quintin McGarel Hogg, Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone, known as the 2nd Viscount Hailsham between 1950 and 1963, at which point he disclaimed his hereditary peerage, was a British barrister and Conservative politician.

Like his father, Hailsham was considered to be a contender for the leadership of the Conservative Party. He was a contender to succeed Harold Macmillan as prime minister in 1963, renouncing his hereditary peerage to do so, but was passed over in favour of the Earl of Home. He was created a life peer in 1970 and served as Lord Chancellor, the office formerly held by his father, in 1970-74 and 1979-87.

Contents

Background

Born in London, Hogg was the son of Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham, who was Lord Chancellor under Stanley Baldwin, and grandson of Quintin Hogg, a merchant, philanthropist and educational reformer, and an American mother.[1] He was educated at Eton College, where he was a King's Scholar and won the Newcastle Scholarship in 1925. He then entered Christ Church, Oxford, as a Scholar, and he was President of the Oxford University Conservative Association and of the Oxford Union. He took Firsts in Honours Moderations in 1928 and in Literae Humaniores in 1930. He was elected to a Prize Fellowship in Law at All Souls College, Oxford, in 1931.[2] He was called to the bar by Lincoln's Inn in 1932. The middle name McGarel, comes from Charles McGarel, who had large holdings of slaves, and who financially sponsored Quintin Hogg's grandfather, also called Quintin Hogg, who was McGarel's brother-in-law.[3] He spoke in opposition to the motion "That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country" in the 1933 King and Country debate at the Oxford Union.

Politics and Second World War

Hogg participated in his first election campaign in the 1924 general election, and all subsequent general election campaigns until his death. In 1938, Hogg was chosen as a candidate for Parliament in the Oxford by-election. This election took place shortly after the Munich Agreement and the Labour candidate Patrick Gordon Walker was persuaded to step down to allow a unified challenge to the Conservatives; A. D. Lindsay, the Master of Balliol College fought as an 'Independent Progressive' candidate. Hogg narrowly defeated Lindsay, who was said to be horrified by the popular slogan of "Hitler wants Hogg".

Hogg voted against Neville Chamberlain in the Norway Debate of May 1940, and supported Winston Churchill. He served briefly in the desert campaign as a platoon commander with the Rifle Brigade during the Second World War. His commanding officer had been his contemporary at Eton; after him and the second-in-command, Hogg was the third-oldest officer in the battalion. After a knee wound in August 1941, which almost cost him his right leg, Hogg was deemed too old for further front-line service, and later served on the staff of General "Jumbo" Wilson before leaving the army with the rank of major. In the run-up to the 1945 election, Hogg wrote a response to the book Guilty Men, called The Left Was Never Right.

Conservative minister

Hogg's father died in 1950 and Hogg entered the House of Lords, succeeding his father as the second Viscount Hailsham. Believing his political career to be over he concentrated on his career at the bar for some years, taking silk in 1953[4] and becoming head of his chambers in 1955, succeeding to Kenneth Diplock.[2] When the Conservatives returned to power under Churchill in 1951, he refused to be considered for office. In 1956, he refused appointment as Postmaster-General under Anthony Eden on financial grounds, only to accept appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty six weeks later.[2] His appointment, however, had to be delayed because of the Crabb affair.

As First Lord, Hailsham was briefed about Eden's plans to use military force against Egypt, which he thought were 'madness'. Nevertheless, once Operation Musketeer had been launched, he thought that Britain could not retreat until the Suez Canal had been captured. When, in the middle of the operation, Lord Mountbatten of Burma threatened to resign as First Sea Lord in protest, Hailsham ordered him in writing to stay on duty: he believed that Mountbatten was entitled to be protected by his minister, and that he was bound to resign if the honour of the Navy was impaired by the conduct of the operation. Hailsham remained critical of the actions of the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Harold Macmillan, during the crisis, believing that he had suffered from a failure of nerve.

Hailsham became Minister of Education in 1957 under Macmillan, holding the office for eight months, before accepting appointment as Lord President of the Council and Chairman of the Conservative Party in September 1957.[2] During his term as Party Chairman, the Conservative Party won a notable victory in the 1959 general election, which it had been predicted to lose. Nevertheless, shortly after the election, Hailsham was sidelined, and was made Minister for Science and Technology, serving in that post until 1964. His tenure as Science Minister was successful, and he was later elected to the Royal Society under Statute 12 in 1973.[2]

Concurrently, Hailsham was Lord Privy Seal between 1959 and 1960, Lord President of the Council between 1960 and 1964, and Leader of the House of Lords between 1960 and 1963, having been Deputy Leader between 1957 and 1960. He was also given a number of special assignments by Macmillan, becoming Minister with special responsibility for Sport from 1962 to 1964, for unemployment in the North-East between 1963 and 1964 and for higher education between 1963 and 1964. Hailsham, who had little interest in sports, thought little of his appointment as de facto Sports minister, later writing that "[t]he idea of a Minister for Sport has always appalled me. It savours of dictatorship and the nastiest kind of populist or Fascist dictatorship at that."

Hailsham appeared before the Wolfenden Committee to discuss homosexuality. The historian Patrick Higgins said that he used it as "an opportunity to express his disgust". He stated "The instinct of mankind to describe homosexual acts as "unnatural" is not based on mere prejudice" and that homosexuals were corrupting and "a proselytising religion".[5]

In June 1963 when his fellow Minister John Profumo had to resign after admitting lying to Parliament about his private life, Hailsham attacked him savagely on television. The Labour MP Reginald Paget called this "a virtuoso performance of the art of kicking a friend in the guts". He added, "When self-indulgence has reduced a man to the shape of Lord Hailsham, sexual continence involves no more than a sense of the ridiculous".[6]

Disclaimer of peerage and Conservative Party leadership bid

Hailsham was Leader of the House of Lords when Harold Macmillan announced his sudden resignation from the premiership for health reasons at the start of the 1963 Conservative Party conference. At that time there was no formal ballot for the Conservative Party leadership.[7] Hailsham, who was at first Macmillan's preferred successor, announced that he would use the newly enacted Peerage Act to disclaim his title and fight a by-election and return to the House of Commons. His publicity-seeking antics at the Party Conference (such as feeding his baby daughter in public, and allowing his supporters to distribute "Q" (for Quintin) badges) were considered vulgar at the time, so Macmillan did not encourage senior party members to choose him as his successor.

Eventually, on the advice of Macmillan, The Queen chose the Earl of Home to succeed Macmillan as prime minister. Hailsham nevertheless renounced his peerage on 20 November 1963, becoming again Quintin Hogg. He was returned as MP for St Marylebone, his father's old constituency, in a by-election in December 1963.

Hogg as a campaigner was known for his robust rhetoric and theatrical gestures. He was usually in good form in dealing with hecklers, a valuable skill in the 1960s, and was prominent in the 1964 general election. One evening when giving a political address, he was hailed by his supporters as he leaned over the podium pointing at a long-haired heckler. He said, "Now, see here, Sir or Madam whichever the case might be, we have had enough of you!" The police ejected the man and the crowd applauded and Hogg went on as if nothing had happened. Another time, when a Labour Party supporter waved a Harold Wilson placard in front of him, Hogg smacked it with his walking-stick.

Lord Chancellorship

Hogg served in the Conservative shadow cabinet during the Wilson government, and built up his practice at the bar where one of his clients was the Prime Minister and political opponent Harold Wilson.[8] When Edward Heath won the 1970 general election he received a life peerage as Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone, of Herstmonceux in the County of Sussex, and became Lord Chancellor. Hogg was the first to return to the House of Lords as a life peer after having disclaimed an hereditary peerage. Hailsham's choice of Lord Widgery as Lord Chief Justice was criticised by his opponents, although he later redeemed himself in the eyes of the profession by appointing Lord Lane to succeed Widgery. His appointment as Lord Chancellor caused some amusement; in October 1962 he had told a journalist (Logan Gourlay of the Daily Express) that when he had inherited his title he had thought that by 1970 if the Tory Government were in power “some ass might make me Lord Chancellor”.

During his first term as Lord Chancellor, Hailsham oversaw the passage of the Courts Act 1971, which fundamentally reformed the English justice by abolishing the ancient assizes and quarter sessions, which were replaced by permanent crown courts. The Act also established a unified court service, under the responsibility of the Lord Chancellor's Department, which as a result expanded substantially. He also piloted through the House of Lords Heath's controversial Industrial Relations Act 1971, which established the short-lived National Industrial Relations Court.

Hailsham announced his retirement after the end of the Heath government in 1974. He popularised the term 'elective dictatorship' in 1976, later writing a detailed exposition, The Dilemma of Democracy. However, after the tragic death of his second wife in a riding accident, he decided to return to active politics, first as a shadow minister without portfolio in the Shadow Cabinets of Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher, then again as Lord Chancellor from 1979 to 1987 under Margaret Thatcher.

Hailsham was widely considered as a traditionalist Lord Chancellor. He put great emphasis on the traditional roles of his post, sitting on the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords more frequently than any of his post-war predecessors.[2] Appointment of deputies to preside over the Lords enabled him to give more time to judicial work, although he often sat on the woolsack himself. He was protective of the English bar, opposing the appointment of solicitors to the High Court and the extension of their rights of audience. He was, however, responsible for implementing the far-reaching 1971 reform of the courts system, and championed law reform and the work of the Law Commission.

Retirement

After his retirement, Hailsham vigorously opposed the Thatcher government's plans to reform the legal profession. He opposed the introduction of contingency fees, observing that the professions were "not like the grocer's shop at the corner of a street in a town like Grantham" (Hansard 5L, 505.1334, 7 April 1989)[9] and arguing that the Courts and Legal Services Act (1990) disregarded "almost every principle of the methodology which law reform ought to attract" and was no less than an attempt to "nationalise the profession and part of the judiciary" (Hansard 5L, 514.151, 19 December 1989).[2]

Towards the end of his life Hailsham suffered from depression, which he managed somewhat by his lifelong love of classical literature.[2]

Hailsham remained an active if semi-detached member of the governing body of All Souls College almost until his death.[2]

Event Participated in

| Event | Start | End | Location(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderberg/1967 | 31 March 1967 | 2 April 1967 | St John's College (Cambridge) UK United Kingdom | Possibly the only Bilderberg meeting held in a university college rather than a hotel (St. John's College, Cambridge) |

References

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gm35tFTtsuc

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-76372

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20200615101719/https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/6914

- ↑ https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/39827/page/2119

- ↑ Higgins, Patrick (1996), Heterosexual Dictatorship, London: Fourth Estate, p. 35

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/greatparliamenta0000parr

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20131215133413/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/4245578.stm

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/11/newsid_2542000/2542413.stm

- ↑ Thatcher's father had been a grocer in Grantham.